Crowdsourcing Journalism Rates

For the last few years I’ve been keeping a list of editors, word rates, contact details and brief notes on different magazine and website editors with my colleagues at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. It was crowdsourcing on a relatively small scale to help us figure out where the best home for our writing would be. However, I’ve come to realize that the list might also be useful for another, perhaps more noble goal. So I’ve scraped off the personal and identifying details and added a few new columns.

For the last few years I’ve been keeping a list of editors, word rates, contact details and brief notes on different magazine and website editors with my colleagues at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. It was crowdsourcing on a relatively small scale to help us figure out where the best home for our writing would be. However, I’ve come to realize that the list might also be useful for another, perhaps more noble goal. So I’ve scraped off the personal and identifying details and added a few new columns.

I’m throwing the database online and inviting writers from all over the world to add what they know about the size of the market. Help out and contribute by clicking on this link. Lets figure out what every magazine pays per word, how many features are in each book, and what they charge for advertising.

It’s a Google Doc, and pretty easy to update and modify. I’ve filled in what blanks that I could, but someone should probably check my numbers. Most advertising rates are easy to find on company media kits like the one Conde Nast publishes publicly.

The reason for this, of course is that last week’s post on how much writing in America is actually worth struck a nerve. Many people were skeptical that magazines might really only pay out $3.6 million a year for their feature wells. The number seems absurdly small. And they might be right. Various commenters mentioned that the New Yorker alone must dish out almost $2 million annually on stories. Tom McGeveren wrote that his own publication (which turned out to be the newspaper the New York Observer) commanded a $3.5 million dollar budget on its own. However everyone seemed to understand the overall point writers get only a tiny sliver of the overall publishing revenues of mainstream magazines.

At the end of the day, almost no matter what set of numbers you crunch I’m almost certain that we will find that feature writing is such an insignificant amount that the advertising revenue from a single issue of one magazine should be able to cover the entire feature budget of all the magazines in America for an entire year. For instance: the December 2014 issue of Wired had 87 full page ads. At the prices listed in the media that would have been worth almost $15 million. Even if we assume that they dolled out a 50% discount to every advertiser, that’s still $7.5 million. The writer’s cut would have been less than $50,000, or about 0.6%.

A full market analysis should not rely only on back of the envelope math. Understanding the total value of words in America is going to require some fairly sophisticated work, as well as information from every sector of the writing world. Jonah Ogles, an editor at Outside, called for writers to get involved and start sharing data. So I’ve decided to follow up. Lets figure this thing out and maybe, just maybe, it will give us a tool to demand a slightly bigger piece of that overall publishing pie.

How much are words worth?

Writers tend to keep their thoughts in the realm of ideas rather than calculate the seemingly mundane matter of the mechanics of the trade. However, a few months ago I sat down in a Chinese restaurant with a friend of mine who writes for the New Yorker and we agreed to leave our narrative musings to the side and think about practicalities. We were going to try to figure out how much the printed word is worth in America today.

Writers tend to keep their thoughts in the realm of ideas rather than calculate the seemingly mundane matter of the mechanics of the trade. However, a few months ago I sat down in a Chinese restaurant with a friend of mine who writes for the New Yorker and we agreed to leave our narrative musings to the side and think about practicalities. We were going to try to figure out how much the printed word is worth in America today.

We wanted to calculate how many feature stories the top magazines in America assign every year, and how much they typically pay their writers for the assignments. The list was only going to be for the top publications in America–the ones that pay between $1.50-$5 per word and that comprise the top tier of journalism. These are the magazines that line the shelves of airport bookstores everywhere and the ones that we write for pretty regularly. Think The New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, Atlantic, Wired, Men’s Journal, Rolling Stone, Playboy, Vanity Fair, Mother Jones, O, The Atavist, and the dozen or so other magazines that sits on the tops of toilet tanks and the tables of dentist offices from Seattle to Orlando.

It was back of the envelope math at best, but as far as either one of us could determine, it was the first time anyone had tried to figure out how biG the pie was for long form freelance writing in America. There are hundreds of amazing writers in the country, delving into stories that drive the national conversation on everything from politics to the cult of celebrity to human rights abuses to cutting edge scientific and technological discoveries. These are the types of pieces that we make a living on, and ones that, frankly, we feel are important to write.

After ten minutes listing the average number of features in each magazine multiplied by the number of issues annually we had a number: 800. On average these stories would run at about 3000 words and pay $1.50 per word. It was only a ball-park estimate of the overall freelance writing market cap. But it was also a rather depressing one. Let me put this in bold so it stands out on the page.

The total market for long form journalism in major magazines in America is approximately $3.6 million. To put it another way: the collective body of writers earned less than Butch Jones, a relatively unknown college football coach, earned in a single year.

$3.6 million. That’s it. And the math gets even more depressing. If we assume that writers should earn the average middle class salary of $50,000 a year, then there’s only enough money in that pot to keep 72 writers fully employed. And, of course, those writers would have to pen approximately 11 well thought out and investigated features per year–something that both my friend and I knew was almost impossible.

Now, it could be that our estimate was a little low. But even if you double it–a number that is almost certainly far and above the size of the actual feature market, then we are collectively still barely scraping above $7 million paid out by magazines in word rates every year. According to Small Business Chronicle, the overall magazine publishing industry generates a total revenue of $35-40 billion a year. While that number includes lots of publications that are not in our sample, it does give at least some sense OF how small a slice of the pie writers actually earn.

Another way to figure out what the total publishing industry is worth is to check out the advertising rates that mainstream magazines publish on their websites. Take Wired, for example – not to pick on them, but because they are a representative of the some of the best journalism that exists in the country today. According to its media kit, a single page of advertising sells for $141,680. (And that’s not even the top of the market. A full page ad in GQ sells for more than $180,000). Multiply that by the number of full page ads in a single issue of Wired (about 30) and you get about $4.6 million in gross revenues per issue of the magazine.

Think about that for a second. A single issue of one major American magazine generates more gross revenue than what the entire magazine industry pays out in word rates over an entire year. If you figure that Wired spends about $30,000 on words in any given issue then a little more back of the envelope math says that words account for only 0.6% of the magazine’s revenue.

As a writer, this state of affairs horrifies me. I feel strongly that writers contribute more than just 0.6% of value to the overall magazine industry. Yes, magazines have a host of expenses–printing, distributing, editing, fact checking, office overhead and marketing all have a cost. But there is also something deeply sick in how little writers’ work is actually valued by the industry.

__

This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

**Stealth edit after some very good criticism **

A lot of people have raised good points at how my numbers are probably low. See the comments on Romenesko’s blog, for some whip-smart critique. I’ll address them in a future post, but I do want to make one quick correction in relation to online advertising rates that really wasn’t properly addressed above.

Most magazines list an aspirational price in their media kit and then give steep discounts to advertisers. I’m a bit sorry to keep picking on them, but I happen to have the December issue of Wired on my desk right now and I just recounted the ads. It was a fatter book than usual. There were 87 full page ads as well as numerous foldouts and a back cover. At the full media kit rate that is about $15 million in gross revenue for that issue. But they probably gave huge discounts to their clients. Lets say it was of 50% per page. That’s $7.5 million in gross advertising revenue. There were 5 features which means a total word count of about 25,000. Include FOB and other stuff it probably comes out to 40,000 words (I’m being generous). At the standard word rate ($2) that would come out to approximately 1% of that issue’s revenue.

**Stealth Edit #2**

Many people have suggested that 800 features is too low low. Lets try to come up with a fairer number. Most consumer magazines (think Details, GQ, Rolling Stone, Atlantic etc) run 2-3 features an issue. The number used to be 4-5, but it went down in the recession. Can we agree then that the average magazine would run about 36 features a year? The New Yorker runs 3 features a week, NYTm about the same. They have 50 issues a year and that makes for 150 stories each year for these sorts of magazines. Lets say there are 4 magazines like this (I can’t think of who they would be). The other 20 magazines run 36 features a year. So we revise the number of features as 1,320 per year. The total payout for these stories would come to about $8 million. Now consider that the December issue of Wired alone brought in $7.5 million even after a steep advertiser discount. One issue of one magazine still can cover the almost the entire cost of all features in America in a given year.

The Contract that Kills Journalism

I’m not sure when it started, but there’s a dangerous trend in the publishing industry to leech value from a writer’s work and make it almost impossible to earn a real living off of journalism. Yes, yes, we all know that media revenues are declining and even 100 year-old publications like The New Republic are teetering on the verge of extinction. For freelance journalists this has meant a general decline in word rates from a high in 1999 of $5/word at the top publications to as a low as $0.50/word at once-mighty institutions. Some publications now only pay their writers base on per-click, which as the venerable Erin Biba once said “is bullshit“.

I’m not sure when it started, but there’s a dangerous trend in the publishing industry to leech value from a writer’s work and make it almost impossible to earn a real living off of journalism. Yes, yes, we all know that media revenues are declining and even 100 year-old publications like The New Republic are teetering on the verge of extinction. For freelance journalists this has meant a general decline in word rates from a high in 1999 of $5/word at the top publications to as a low as $0.50/word at once-mighty institutions. Some publications now only pay their writers base on per-click, which as the venerable Erin Biba once said “is bullshit“.

But, I’m not writing to lament the decline of freelance revenues. I’m writing about something far more sinister: the way that publications today often demand that writers not only accept far less pay than they have received in the past, but also forfeit any rights over the work that they produce. While most new writers don’t think about much more than the pay they get for their words, a good story can go on to have a long life in several different mediums. The most lucrative of which are book, movie and TV deals. In those cases a writer could stand to make upwards of six figures for the research and narrative work that they put in up front. Indeed, many of the best movies of the last ten years started out as magazine stories (Argo, Hurt Locker, Erin Brockovich, Adaptation, Coyote Ugly, Boogie Nights, Big Love to name just a few).

Late last month I got ahold of Newsweek’s standard contract that one of my correspondents sent me. Hidden on the second page was this clause:

Assignment and Ownership of Intellectual Property. Writer hereby understands and agrees that all Articles submitted to, and published by, Company under this Agreement shall be considered works for hire as contributions to a collective work. This confers on the Company all right, title and interest, including copyright, in and to the Article(s), throughout the world. Further, to the extend any intellectual property right does not pass pursuant to a work for hire, Writer hereby assigns to Company all right, title, interest and copyright in and to the Article(s), and all previously submitted articles of Writer. In addition to the foregoing, Writer grants the Company a perpetual, worldwide, royalty-free, paid-up non-exclusive transferable license under copyright to reproduce, distribute, display, perform, translate or otherwise publish individually or as part of a collective work your Article(s) and all previously submitted articles to the Company, in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which it can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device, including without limitation the rights to archive, republish, edit, repackage or revise any Article in any manner as Company sees fit.

In short, this says that whatever you write for Newsweek is their property. It is as if they came up with the idea themselves, reported it in the field and typed it up on their own computers and the writer didn’t even exist. Work-for-hire contracts are always biased against an independent contractor, but this one is particularly onerous. Essentially this says that the writer has no copyright, no ownership, nothing whatsoever other than the $.50-$.75/word they were offering as “payment”. Never-mind that a typical investigative piece might take weeks, or even months to report, and that the final payment might well be below minimum wage, but as a writer you don’t even have the option to take the story idea that you developed and turn it into something bigger and potentially profitable. You can’t reprint it in a foreign publication, can’t sell the movie rights. Nothing. It would be one thing if this language was in a contract for actual employment, where you might get healthcare, retirement benefits and business cards.

This sort of language makes my blood boil. I’ve seen things like this with other publications (Conde Nast, for instance, has some pretty harsh language around movie rights), but nothing quite as bad as this.

This, my gentle readers, is why the future of journalism is in such perilous standing. If magazines don’t pay journalists, and then also make it impossible for them to otherwise earn a real living off of their work then one day there will be no journalists to work with.

My advice to any journalist faced with a clause like this: don’t sign it. Post your story on your personal blog, or sell it to another publication.

__

UPDATE: This, of course is pretty bad news for freelancers, but there are a few ways to fight back. I recently started offering an online video course teaching some of the tricks that I use to negotiate better contracts, and grow my freelancing business from nothing to becoming a New York Times bestselling author. It might be useful for you. Check it out.

National Novel Writing Month

I don’t write novels, but this morning I got a message from the website Webucator asking me for my thoughts on National Novel Writing Month. In particular they wanted to know what it means to write for a living. Regular readers will remember that I recently published a short ebook on the freelance writing career path called The Quick and Dirty Guide to Freelance Writing about how to attain that elusive dream of quitting your day job and working for yourself. So, perhaps, they wondered, I could share a few thoughts on how to write for a living.

I don’t write novels, but this morning I got a message from the website Webucator asking me for my thoughts on National Novel Writing Month. In particular they wanted to know what it means to write for a living. Regular readers will remember that I recently published a short ebook on the freelance writing career path called The Quick and Dirty Guide to Freelance Writing about how to attain that elusive dream of quitting your day job and working for yourself. So, perhaps, they wondered, I could share a few thoughts on how to write for a living.

What were your goals when you started writing?

Sometimes I feel like I didn’t choose to be a writer, but that writing chose me.I’d failed or been fired from every other job I’d tried over the years and writing was the only thing that I was ever good at. Part of the problem, of course, is that I have an almost adolescent rejection of authority and working on other people’s projects always seemed less fulfilling than working on my own things. I also have a predilection for exploration and adventure. Writing has given me an excuse to spend months at a time pursuing strange and unusual subjects and call it a career. As I mention in the book, my first real assignment came after I’d dropped out of graduate school and enrolled in a clinical trial for the erectile dysfunction drug Levitra. I thought that it was hilarious that I was going to be stuck in a room with 30 other dudes on penis-poppers and decided to write to Nerve.com to see if they wanted a feature on the subject. They did, and a writing career was born.

What are your goals now?

At first it was good enough to see my name in a magazine or newspaper. Getting a byline was such a buzz that I would probably have done it for free. Now, however, the luster has worn off a bit and I’m a little more picky about what sorts of assignments I take. A lot of publications don’t treat their writers very well. Boiler-plate contracts are often rigged against the writer and payment can take forever if the magazine is even a little bit disorganized. So while I still love the work (i.e. having mini adventures in the world and then coming back home and telling people about it) I am much more savvy at making the work that I do build into larger things.

What pays the bills now?

After about six years of freelancing exclusively for magazines I started to diversify my revenue streams. I had a pretty substantial body of work that I controlled the rights to, so I started to poke and prod magazines and newspapers in foreign markets to see if they’d be interested in buying reprints. Some time around 2008 I made $$25,000 on reprinting one story in 15 different countries and I realized that secondary markets could be more lucrative than the initial assignment fee. I began looking for other ways to make money on my writing and compiled some of my best stories into a book called The Red Market. While the book didn’t become an out-of-the-box bestseller, it established me as a serious journalist in a way that simply having a byline in a magazines never could have. It also opened upmarket for paid speaking engagements. I started giving lectures around the United States and Europe on the subject of organ trafficking. I started looking at magazines as incubators more lucrative projects. Now I only write stories in magazines if I plan to build it into something bigger. My third book A Death on Diamond Mountain, started out as a story in Playboy.

Assuming writing doesn’t pay the bills, what motivates you to keep writing?

At this point writing absolutely does pay the bills.

And optionally, what advice would you give young authors hoping to make a career out of writing?

It’s counterintuitive, but the most important thing you can do as a writer is say “No” to assignments. It’s very easy to fall into the trap of believing that simply having a byline is payment enough. This sort of mindset will doom any aspirations that you might have to make writing a living. There are a lot of bad deals out there, and if you don’t stand up for your work then why should you expect someone else to do it for you? Treat your writing career as a business negotiate every deal you have with an eye to building the career that you want.

The Current talks Red Markets

Listen to the CBC’s coverage of “The Red Market” where I talk bone thieves, blood farmers and things that go bump in the night.

Listen to the CBC’s coverage of “The Red Market” where I talk bone thieves, blood farmers and things that go bump in the night.

Tavis Smiley and The Red Market

Tavis Smiley who has one of the most thought provoking talk shows on television, had me on to talk about how red market transactions disproportionately affect poor people and send flesh up the human supply chain.

Tavis Smiley who has one of the most thought provoking talk shows on television, had me on to talk about how red market transactions disproportionately affect poor people and send flesh up the human supply chain.

See the video of the interview on PBS.

New York Times Review

Need a Kidney? A Skull? Just Bring CashMichiko Kakutani June 16 2011Whereas black markets trade in illegal goods like guns and drugs, the “red market,” the journalist Scott Carney says in his revealing if somewhat scattershot new book, trades in human flesh — in kidneys and other organs, in human corneas, blood, bones and eggs. Many of the real-life examples he cites in this chilling volume cannot help but remind the reader of a horror movie, or of Kazuo Ishiguro’s devastating dystopian novel “Never Let Me Go” (2005), in which we learn that a group of children are clones who have been raised to “donate” replacement body parts.

Need a Kidney? A Skull? Just Bring CashMichiko Kakutani June 16 2011Whereas black markets trade in illegal goods like guns and drugs, the “red market,” the journalist Scott Carney says in his revealing if somewhat scattershot new book, trades in human flesh — in kidneys and other organs, in human corneas, blood, bones and eggs. Many of the real-life examples he cites in this chilling volume cannot help but remind the reader of a horror movie, or of Kazuo Ishiguro’s devastating dystopian novel “Never Let Me Go” (2005), in which we learn that a group of children are clones who have been raised to “donate” replacement body parts.

In “The Red Market” Mr. Carney recounts the story of a police raid on a dairy farmer’s land in a small Indian border town that freed 17 people who had been confined in shacks and who said they’d been bled at least two times per week. “The Blood Factory,” as it was called in the local press, he writes, “was supplying a sizable percentage” of the city hospitals’ blood supply.

Mr. Carney also investigates the bone trade in India — for almost 200 years, “the world’s primary source of bones used in medical study” — and tries to track down the head of a grave robbing ring in West Bengal, who, according to police, was pilfering corpses from cemeteries, morgues, and funeral pyres and employed “almost a dozen people to shepherd the bones through the various stages of defleshing and curing.”

A contributing editor at Wired magazine, Mr. Carney writes with considerable narrative verve, slamming home the misery of what he has witnessed with passion and visceral detail. His book does not attempt to provide a comprehensive picture of red markets in the world today. Much of Mr. Carney’s reporting focuses on India (where he lived and worked for a decade), while dealing only cursorily with human organ trafficking in other hot spots like the Philippines and Brazil.

In one chapter Mr. Carney describes an impoverished Indian refugee camp for survivors of the 2004 tsunami that was known as Kidneyvakkam, or Kidneyville, because so many people there had sold their kidneys to organ brokers in efforts to raise desperately needed funds. “Brokers,” he writes, “routinely quote a high payout — as much as $3,000 for the operation — but usually only dole out a fraction of the offered price once the person has gone through it. Everyone here knows that it is a scam. Still the women reason that a rip-off is better than nothing at all.” For these people, he adds, selling organs “sometimes feels like their only option in hard times”; poor people around the world, in his words, “often view their organs as a critical social safety net.”

Toward the end of the book Mr. Carney notes that “criminal and unethical red markets are far smaller than their legitimate counterparts.” According to the World Health Organization, he writes, “about 10 percent of world organ transplants are obtained on the black market.” But he emphasizes that “red markets are now larger, more pervasive, and more profitable than at any other time in history,” and that “globalization has made the speed and complexity of these markets bewildering.”

The most alarming allegations cited in this book come from a 2006 report released by David Kilgour, a former member of the Canadian Parliament, and the human rights lawyer David Matas, which suggested that vital organs (including kidneys, corneas and livers) had been harvested on a large scale from executed members of Falun Gong, a banned spiritual group in China. The Chinese government denied the allegations.“

No one is saying the Chinese government went after the Falun Gong specifically for their organs,” Mr. Carney writes, “but it seems to have been a remarkably convenient and profitable way to dispose of them. Dangerous political dissidents were executed while their organs created a comfortable revenue stream for hospitals and surgeons, and presumably many important Chinese officials received organs.”

Mr. Carney is not able to verify the Kilgour-Matas report independently. For that matter, his overall approach here tends to be heavily anecdotal and selective, focusing on horror stories like the kidnapping of a young Indian boy, who, the police said, was brought to an orphanage “that paid cash for healthy children” and then “exported the children to unknowing families abroad.”

As Mr. Carney sees it: “Eventually, red markets have the nasty social side effect of moving flesh upward — never downward — through social classes. Even without a criminal element, unrestricted free markets act like vampires, sapping the health and strength from ghettos of poor donors and funneling their parts to the wealthy.”

His book is filled with harrowing stories in which the destitute and desperate end up sacrificing their bodies for the sake of a few dollars that fail to change their lives.

In one chapter Mr. Carney writes that most egg donors in Cyprus — which “had more fertility clinics per capita than any other country” — come from the relatively small population of poor Eastern European immigrants who are “eager to sell their eggs at any price.” A donor in Cyprus will probably get paid a few hundred dollars for her eggs, Mr. Carney estimates, while customers — often from Western Europe — will pay $8,000 to $14,000 for full-service egg implantation with in vitro fertilization in Cyprus, “about 30 percent less than the next cheapest spot in the Western world.”

Globalization has also brought what Mr. Carney calls the “fertility tourism industry” to India, which, he says, “legalized surrogacy in 2002 as part of a larger effort to promote medical tourism.” At the Akanksha Infertility Clinic (which was featured in an “Oprah” segment), he says, surrogates, who make between $5,000 and $6,000, live in residential units, where “they will spend their entire pregnancies under lock and key.” The clinic charges between $15,000 and $20,000 for the entire process, he reports, “whereas in the handful of American states that allow paid surrogacy, bringing a child to term can cost between $50,000 and $100,000.”

“Before India, only the American upper classes could afford a surrogate,” Mr. Carney writes. “Now it’s almost within reach of the middle class. While surrogacy has always raised ethical questions, the increasing scale of the industry makes the issue far more urgent. With hundreds of new clinics poised to open, the economics of surrogate pregnancies are moving faster than our understanding of its implications.”

In addressing such ethical questions throughout this grisly but fascinating volume, Mr. Carney forces the reader to think about the moral issues raised by advances in medicine. His book also asks us to re-evaluate the roles that privacy, anonymity and altruism play in the current “system of flesh exchange” — which, as disturbing as it is to contemplate, is subject, like those for other commodities, to the brutal marketplace equations of supply and demand.

"Invasion of the Body Snatchers"

Invasion of the Body SnatchersKidneys are the most popular — bought and sold on the global black market at a rate of at least 20,000 per year. Blood, tissue, skin, corneas and eggs are also highly valued. Human bones are a centuries-old mainstay.

Invasion of the Body SnatchersKidneys are the most popular — bought and sold on the global black market at a rate of at least 20,000 per year. Blood, tissue, skin, corneas and eggs are also highly valued. Human bones are a centuries-old mainstay.

The demand outstrips the supply, and so millions of variations on that old urban legend — some unsuspecting victim waking up in a bathtub in Vegas, missing a kidney — actually exist: People snatched off the street in India and China, held for years as chained-up blood donors. Prisoners in China forced to donate body parts, plucked apart, sometimes alive, sometimes without anesthesia. Entire villages, like the Baseco slum in the Philippines, where the bulk of inhabitants have only one kidney — having sold the other off for a few hundred dollars to pay rent or buy food or medicine for a sick relative.

Read Maureen Callahan’s full story at the NY Post

NPR: Blood, Bones And Organs

Journalist Scott Carney figures he’s worth about $250,000, but that number isn’t based on his savings or his assets; it’s what Carney thinks his body would fetch if it were broken down into individual parts and sold on what he calls the “red market.” In his new book, also called The Red Market, Carney explores the shadowy but lucrative global marketplace for blood, bones and organs. He tells NPR’s Melissa Block that despite being underground, there’s no question the red market is thriving. “It’s really hard to get accurate figures on what the illegal market is on body parts, but I’m figuring it’s definitely in the billions of dollars,” Carney says.

Journalist Scott Carney figures he’s worth about $250,000, but that number isn’t based on his savings or his assets; it’s what Carney thinks his body would fetch if it were broken down into individual parts and sold on what he calls the “red market.” In his new book, also called The Red Market, Carney explores the shadowy but lucrative global marketplace for blood, bones and organs. He tells NPR’s Melissa Block that despite being underground, there’s no question the red market is thriving. “It’s really hard to get accurate figures on what the illegal market is on body parts, but I’m figuring it’s definitely in the billions of dollars,” Carney says.

‘When You’re At Your Most Desperate Place … The Brokers Come In’ As part of his research, Carney visited an Indian refugee camp for survivors of 2004’s massive tsunami. Today, the camp is known by the nickname Kidneyvakkam, or Kidneyville, because of how common it is for the women who live there to sell their kidneys. “The women are just lined up,” Carney says. “They have their exposed midriffs and there are all these kidney extraction scars because when the tsunami happened, all these organ brokers came in and realized there were a lot of people in very desperate situations and they could turn a lot of quick cash by just convincing people to sell their kidneys.”

Photos from The Red Market

For six years I didn’t only collect stories from people who supplied their flesh on the red market. I also took pictures. Here is a small set of photos that appeared in the book. Above is Fatima whose daughter Zabeen was kidnapped from a slum in Chennai and sold to an Australian family through a network of unwitting adoption agencies. Please don’t reproduce these without my permission.

For six years I didn’t only collect stories from people who supplied their flesh on the red market. I also took pictures. Here is a small set of photos that appeared in the book. Above is Fatima whose daughter Zabeen was kidnapped from a slum in Chennai and sold to an Australian family through a network of unwitting adoption agencies. Please don’t reproduce these without my permission.

Click here to see the gallery.

India's Maoists

Since 2000 more than 10,000 people have died and 150,000 displaced by a Maoist insurgancy in India. In 2007 I traveled to Chhattisgarh, India with Jason Miklian to report how a police-funded civilian counter insurgency called “Salwa Judum” had only made the conflict worse. Now with warlords, communist ideologues and out of control military forces there are few places for civilians to find safety. While this story never appeared in a major publication, a later version that traced the connections between the mining industry and Maoism appeared in Foreign Policy in September 2010 under the title “Fire in the Hole”

Since 2000 more than 10,000 people have died and 150,000 displaced by a Maoist insurgancy in India. In 2007 I traveled to Chhattisgarh, India with Jason Miklian to report how a police-funded civilian counter insurgency called “Salwa Judum” had only made the conflict worse. Now with warlords, communist ideologues and out of control military forces there are few places for civilians to find safety. While this story never appeared in a major publication, a later version that traced the connections between the mining industry and Maoism appeared in Foreign Policy in September 2010 under the title “Fire in the Hole”

Click here to see the photo gallery

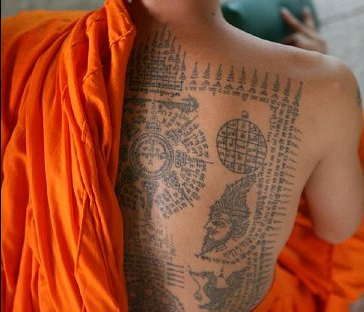

Thai Protection Tattoos

Can a tattoo stop a bullet? A centuries old thai tattoo tradition teaches that indeed, the sacred scriptures can have protective powers. In 2007 I traveled to the remote wat bang pra temple to interview the artistic masters who have spent their lives perfecting the art. I reported the story for National Public Radio which you can listen to here. But what what is a radio story without great photos?

Can a tattoo stop a bullet? A centuries old thai tattoo tradition teaches that indeed, the sacred scriptures can have protective powers. In 2007 I traveled to the remote wat bang pra temple to interview the artistic masters who have spent their lives perfecting the art. I reported the story for National Public Radio which you can listen to here. But what what is a radio story without great photos?

Click here to see the gallery of photos here.

Salon Review: Flesh for sale

During the mid-2000s, Scott Carney was living in southern India and teaching American anthropology students on their semester abroad when one of his charges died, apparently a suicide. For two days, he watched over her body while the provincial police investigated her death, reporters bribed their way into the morgue to photograph the newsworthy corpse, local doctors performed an autopsy, and ice had to be rounded up to retard decomposition. Finally, his boss asked Carney to take pictures of the girl’s mangled remains for analysis by forensic experts back in the States.

During the mid-2000s, Scott Carney was living in southern India and teaching American anthropology students on their semester abroad when one of his charges died, apparently a suicide. For two days, he watched over her body while the provincial police investigated her death, reporters bribed their way into the morgue to photograph the newsworthy corpse, local doctors performed an autopsy, and ice had to be rounded up to retard decomposition. Finally, his boss asked Carney to take pictures of the girl’s mangled remains for analysis by forensic experts back in the States.

(review by Laura Miller)

Border Wars

Bangladesh shares a border with only two other countries: the republic of India and the dictatorship of Burma. With climate change threatening much of the low-lying country refugees will have to go somewhere. And India has decided to prepare for the influx by building a wall and shooting anyone who tries to cross it. In January 2011 I traveled to Bangladesh and India with Jason Miklian and Kristian Hoelscher on an assignment for Foreign Policy.

Bangladesh shares a border with only two other countries: the republic of India and the dictatorship of Burma. With climate change threatening much of the low-lying country refugees will have to go somewhere. And India has decided to prepare for the influx by building a wall and shooting anyone who tries to cross it. In January 2011 I traveled to Bangladesh and India with Jason Miklian and Kristian Hoelscher on an assignment for Foreign Policy.

The Last Calligraphers

The age of calligraphy died when British soldiers toppled the Mughal courts. It’s hard to remember that there was a time before the age of computers when penmanship was considered one of the highest art forms. Outside of a some particularly ornate wedding invitations and hand-written copies of the Koran there is little need for formally trained Urdu calligraphers. That is, except for one small ink-stained corner of Chennai where the world’s last hand written newspaper still churns out 20,000 broad sheets a day.

The age of calligraphy died when British soldiers toppled the Mughal courts. It’s hard to remember that there was a time before the age of computers when penmanship was considered one of the highest art forms. Outside of a some particularly ornate wedding invitations and hand-written copies of the Koran there is little need for formally trained Urdu calligraphers. That is, except for one small ink-stained corner of Chennai where the world’s last hand written newspaper still churns out 20,000 broad sheets a day.